“2001: A Space Odyssey” has a very unusual characteristic among book to film adaptations, in that it was developed simultaneously as a novel and a film by author Arthur C. Clarke and filmmaker Stanley Kubrick. In the early 1960’s, Kubrick was looking for a sci-fi project to develop into what would be the first serious-minded sci-fi film ever (as all science fiction films up to that point exclusively featured monsters, alien invasions and sex), and through a mutual acquaintance, was hooked up with renowned science contributor and author Clarke. They spent several years together brainstorming ideas and spit balling before they came up with what would become 2001. As a result of their very close collaboration during the production of both pieces of art, 2001 the movie and 2001 the novel work as complementary pieces, informing each other and helping to create a more whole picture. That isn’t to say there are no deviations between the two works, but even with these deviations, the essential truths and themes are kept intact.

The story is the same for both film and novel: it begins at the Dawn of Man, in which man-apes struggle to survive in their harsh environments populated with predators, and when a strange monolith shows up out of nowhere, it springboards the man-apes evolutionary process to the next stage, here personified by the invention of the first tool – a bone used a hammer and as a weapon. It is with this sequence the main difference between movie and book is demonstrated. When the monolith appears in Clarke’s novel and Moonwatcher (the “hero” man-ape) sits down in front of it, Clarke explains how Moonwatcher is unaware of the programming going on in his own mind. It’s a lot like in The Matrix when they download information directly into their brains from a computer. The monolith enabled Moonwatcher’s brain to think in different ways and to experience his world differently, and when the Monolith goes away, Moonwatcher is forever changed, and the advances in living that he introduces to his clan enable them to continue to survive and even thrive in their unforgiving and brutal world. in Kubrick’s film, however, all of this is left purposefully ambiguous and symbolic. The apes react to the monolith and this scene is directly followed by the scene in which Moonwatcher discovers alternate uses for discarded bones. The link to evolution does not come directly and explicitly as it does in the novel, but instead through a series of very carefully chosen edits. The monolith directly precedes the tool discovery which directly precedes one of the most famous jump cuts in cinema history – Moonwatcher throws his new tool, the bone, into the air and it tumbles end over end and as it descends it turns into a satellite floating in space, millions of years of evolution captured in two distinct images.

Similarly, these satellites shown in the first moments of the space-age of man are left ambiguous as to their exact nature, although they were originally designed to be nuclear weapons platforms, making the jump cut between the bone-as-a-weapon and satellite-as-a-weapon even more profound. But due to several circumstances, including the agreement at the time between the US and the USSR to never put weapons in space and possible correlations between 2001 and Kubrick’s previous film Dr. Strangelove, Kubrick decides that the nuclear weapon angle was not necessary to the story or themes, and was hence excised. The use of nuclear weapons, however, would find its way into Clarke’s published novel (more on this later).

When the story catches up to 2001, we’re with Dr. Haywood Floyd who takes a routine space shuttle to the moon, where an undisclosed emergency awaits him. Here both the movie and the novel stick very close to each other. Much like in the Dawn of Man section, the nature of the long form novel allows Clarke to get into the head of Dr. Flloyd as he thinks of his travels and informs us of how mankind has progressed to that point. Not only was traveling to the moon a regular occurrence, but a moon base had been established and children had been born on that moon, with their own views of what could possibly meet them on Earth. At one point, Dr. Floyd marvels at what these new generations of space-born children will bring, a concept that is not introduced in the film, and could actually be the basis of it’s own epic story, film or otherwise. Clarke would actually revisit the idea of generations of people being born on bases on other planets in his 1972 novel Rendevous with Rama.

The third section of the story is what most people visualize when thinking of 2001: A Space Odyssey. 18 months after the discovery of another monolith (this time on the moon), mankind embarks on a manned flight to Jupiter. The novel, however, merely uses Jupiter as a gravitational springboard to Saturn. Kubrick was not happy with the effects made to create the rings of Saturn, and opted to change the final destination. Clarke, unencumbered by such restrictions in the written form, kept the original Saturn destination. The ship is populated by a crew of five, with three of those crew members in hibernation, scheduled to be awoken when they reach their destination. The two awake crew members, Dr. Bowman and Dr. Poole, run the entire ship with the aid of the on board computer HAL, and most of what happens in this section is again similar in both movie and book. When HAL makes a possible mistake in predicting a faulty component on the ship, the computer actually goes through a nervous breakdown that makes it murderous. And like all good story villains, HAL’s evil deeds are performed under the guise of doing good, as it sees its actions as the only way to ensure the mission is a success. The exact way it goes about these actions are pretty different between the two stories, but the outcomes are all the same – Dr. Poole is left completely by himself to finish the mission, with HAL taken off line.

The final Stargate and Star-Child portion of the story benefits the most from being familiar with both book and movie. Dr. Bowman, now all alone and with a considerable time lapse in communication between himself and Earth, heads out to discover the third monolith. In Kubrick’s film, when Dr. Bowman finds the monolith, he gets sucked into it and flies through space at ridiculous speeds, and the colors of space fly past him in smears. It’s a crazy visual sequence that at the time was showstopping in its uniqueness, but it is also very abstract and really doesn’t show much. In the novel, however, Dr. Bowman observes much while flying through this stargate, including a portion of space that possessed a white sky with black stars (a negative of the night sky that we are used to seeing) and something of a spaceship way station long since abandoned. Clarke’s descriptions are pretty intense and dynamic, and filmmakers today would be able to replicate these descriptions with computers and digital trickery. But without these tools at his disposal, Kubrick opted for the much more abstract approach to the unknowable.

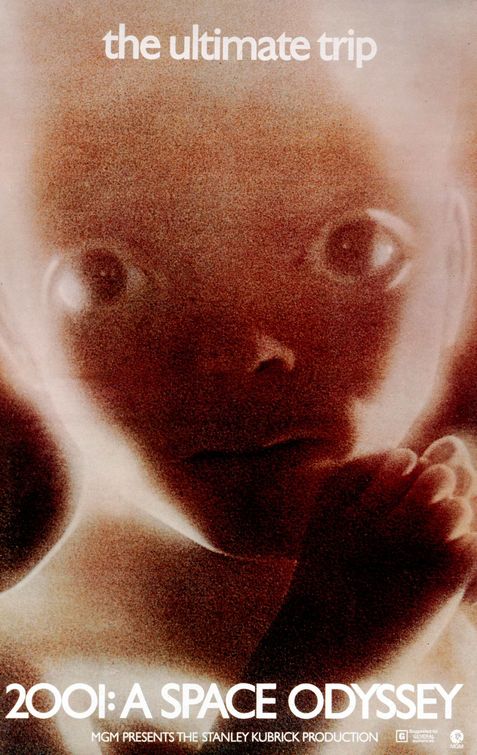

The end of the stargate journey finds Dr. Bowman emerging from his space pod into a hotel room, complete with food, furniture and a working television (the TV is in the novel only). Kubrick shows us several versions of Dr. Bowman living out the end of his life in this room, getting older as he makes his way to his bed. At the foot of his bed appears another monolith, and this is followed by a giant baby floating in space, overlooking Earth. A befuddling ending for sure. But Clarke gets very explicit as to what happens in this section. Dr. Bowman cautiously enters this weird hotel room in the middle of nowhere and discovers that it was set up to make a visitor like him completely comfortable. After eating and showering, he lays down in the bed where he succumbs to sleep, never to wake up again. As he sleeps, his memory and life force are essentially downloaded by an unseen being, presumably the same being that installed the original monolith at the Dawn of Man as a catalyst for mankind’s evolution, and Dr. Bowman ceases to exist as a man and starts to exist as just energy. Dr. Bowman is conscious of his present state and manifests himself as a baby to reflect his infantile state in his new form of existence. In this state, he travels back to Earth, where he hovers in orbit and looks down upon the planet. This is where the nukes come back into play:

“A thousand miles below, he became aware that a slumbering cargo of death had awoken, and was stirring sluggishly in its orbit. The feeble energies it contained were no possible menace to him; but he preferred a cleaner sky. He put forth his will, and the circling megatons flowered in a silent detonation that brought a brief, false dawn to half the sleeping globe.”

Bowman the Star-Child has come back to Earth to essentially dominate it, as there would be nothing in his way from doing whatever he wanted to do. The final lines of the novel are both exciting and harrowing: “For though he was master of the world, he was not quite sure what to do next. But he would think of something.” What is left abstract in Kubrick’s film is made concrete in Clarke’s novel, and though the film version has a much more peaceful ending due to the exclusion of the nukes, it still points to a similar ending, one about the next stages of evolution for mankind, and how ultimately they could be as unknowable to us as our world was unknowable to Moonwatcher.

Very few films and related books have been developed this way, and for Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke, their work together resulted in a pair of towering works of science fiction that would go on to heavily influence both the worlds of filmmaking and writing for years to come, themselves spring boarding the evolution of sci-fi based storytelling.

Originally published on Examiner.com on Dec. 12, 2010.

Click here for all “book-to-film” adaptation articles.

Netflix pick for 4/14/14 – ‘Scrooged’

Netflix pick for 4/14/14 – ‘Scrooged’ #151 – Elbow Drops In Heaven

#151 – Elbow Drops In Heaven Florida Film Festival 2014 review: ‘Strike: The Greatest Bowling Story Ever Told’

Florida Film Festival 2014 review: ‘Strike: The Greatest Bowling Story Ever Told’ Review: ‘Independence Day: Resurgence’

Review: ‘Independence Day: Resurgence’

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.