“Eye in the Sky” is a tight thriller about drone warfare, examining the morality of making these brutal strikes from remote locations and the collateral damage they cause, but also getting into the complexities of coordinating with so many different people to make one crucial decision in a real time situation, and making this all seem that much more immediate and relevant is the current world setting, as the movie name drops real terrorist groups and actual events, driving home the point that this is how things really happen, this is the current state of the war on stateless terror.

“Eye in the Sky” is a tight thriller about drone warfare, examining the morality of making these brutal strikes from remote locations and the collateral damage they cause, but also getting into the complexities of coordinating with so many different people to make one crucial decision in a real time situation, and making this all seem that much more immediate and relevant is the current world setting, as the movie name drops real terrorist groups and actual events, driving home the point that this is how things really happen, this is the current state of the war on stateless terror.

So while being very current and of our time, the story itself is pretty solid in how new questions and obstacles keep popping up, making this a race against the clock type of situation, and as that clock ticks away the circumstances change, things are fluid at all times, and this causes ripples through all the layers of government involved in deciding whether or not to use this one mission to make one strike on one building to kill a small handful of people.

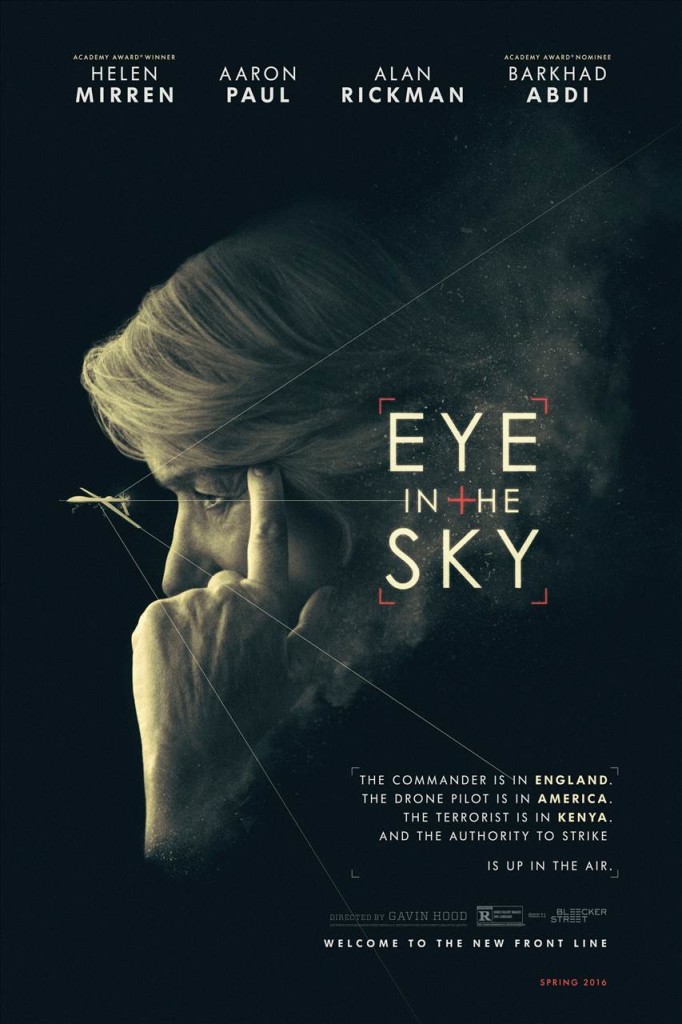

There is a strong element in “Eye in the Sky” of voyeurism, as at least 75% of this film consists of different groups of people watching surveillance footage very tentatively and then having video conferences with each other about it. Leading the charge is Col. Powell (Helen Mirren), heading a surveillance and capture drone mission from a decision room in the UK, with several high ranking government and military officials sitting in another room watching the same footage and conferencing with the Colonel. (Among this group is the great Alan Rickman in his final live action performance, and of course he’s great as he always was.) This drone is flying over Nairobi, Kenya, where several known and very much wanted dead or alive terrorists have entered a safe house, and there is a squad of ground troops there ready to bust in if needed, though that would result in a gun battle that no one wants. And this drone is piloted by a pair of Americans outside Las Vegas (Aaron Paul and Phoebe Fox), two fresh faced twenty-somethings who suddenly find themselves tasked with actually using the weapons they have been assigned.

So there are essentially four locations that they cut back and forth between, and just when they are comfortable enough to drone strike this house and kill these terrorists (British and American citizens, by the way, adding another layer of real world complexity there), a young girl emerges in the shot, setting up just outside the safe house to sell her mother’s bread to people walking by, and this causes the biggest debate of the movie, probably the last half of this film, as they decide whether or not to go ahead, with everyone from the American pilots all the way up to the highest levels of British government questioning whether or not it was worth it to possibly kill this little girl if it meant saving up to eighty people or more in the imminent suicide bombings these terrorists were plotting. It’s not like they were sitting around saying to themselves, “Gee, these terrorists MIGHT be plotting something, but we are not sure really,” because they got a camera in the house and saw them putting together suicide bomb vests for two young men to use in undoubtedly crowded places, so they know for certain if they don’t strike before they leave, many more people will die.

This is definitely not your grandfather’s war movie. And I mean that very literally. The war movies of the 50s and 60s (a hugely popular and profitable genre at the time) were all rah rah for the American war machine, as it was used to first help beat back Kaiser Wilhelm II in WWI and then Adolf and his Nazis in WWII, and these movies celebrated these victories because there was a very strong sense of right versus wrong, of democracy versus fascism, so it was easy to throw John Wayne into these things and make America feel great about war and themselves. Vietnam changed that, and the movies changed with the wars. We are now locked in a war against an amorphous enemy – it’s one thing to go to war against an organized country, it is something entirely different to fight small groups of people dispersed all through a region, in both warring and non-warring countries, making problems for people throughout much of the world. As such the movies of our modern wars reflect this more complex and complicated landscape, which is how we get things like “The Hurt Locker” and “Green Zone” and “In the Valley of Elah.” And you know what else those movies have in common? They did not make much money. But if you “take out the politics” of war movies like this, you get stuff like “Lone Survivor” and “13 Hours” and “American Sniper,” and those movies DID make money because they allowed general audiences to feel okay about looking up to their soldiers and armed forces while not being hit in the face with the possibility of maybe perhaps accidentally seeing a somewhat different and more complex viewpoint of the world around them.

“Eye in the Sky” went with the former, and will leave the rah rah version of the drone war movie to the nice folks making “Top Gun 2,” so this movie is very much taking a complex situation which happens all the time and imagines the chain of command, how people from all over the world from various state departments get pulled away from whatever they are doing, whether that be playing table tennis with the Chinese National team or battling food poisoning in a hotel room while two aides look on, and are forced to debate the merits of such a drastic measure. Well, except for the two Americans who get consulted on this matter, as they are presented as very gung ho, go get them kind of people, real bloodthirsty and callous. One person is practically like, “why the fuck are you even calling me, kill that little girl already, she might grow up to be a terrorist just like the rest of them, gawd, what’s wrong with you, you a bunch of pussies or something? Kill! Kill! Kill!” Seriously, though, that’s how the rest of the world sees us. And thanks to the film “Citzenfour,” we know that for at least a time period, this could have changed since then, the President himself signs off on that week’s list of approved drone strikes every Tuesday morning, and even a piece of jingoistic shit like “London Has Fallen” acknowledges the incredible collateral damage of drone strikes, so this characterization of our military and our government’s willingness to deploy it seems unfortunately spot on, if a bit exaggerated for dramatic effect.

The actual characters in the movie are barely sketched out – Colonel Powell is singular in her objective and seems fine with bending the rules of engagement just slightly to make what she feels is the right decision. The pilots are young and inexperienced, so when they are called upon to kill some folks in Nairobi from their bunkers in Nevada, they feel conflicted about it, finding themselves on the end of a trigger of a very deadly weapon, and they can see the potential collateral damage, which includes maybe just a bit of their conscious, as they have to put that aside if they care to do their jobs. There are no easy answers in “Eye in the Sky” and it doesn’t shy away from the hard questions or any possible brutal aftermath. It does seem as if they may have had some scenes, at least early on, that hinted at some characterization, some back story, especially for the two young pilots, but then all of this got cut to make the movie tighter and faster, and while it is certainly a solid thriller with plenty of tension, the characters involved are all almost entirely just stand ins for actual people, so they can just get to the business of going through the plot. We learn that the little girl likes to hula hoop and the Foreign Minister likes prawns and Colonel Powell’s husband snores and the Lt. General (Rickman) needs to get a toy doll for his daughter or granddaughter or something. That’s it. Otherwise it is drone strike ahoy.

Bonus Episode – The Three Caballeros

Bonus Episode – The Three Caballeros #600 – Decade of ‘Diso

#600 – Decade of ‘Diso Spoiler Bonus Episode – The Dark Tower

Spoiler Bonus Episode – The Dark Tower #531 – Men Be Talking

#531 – Men Be Talking

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.