“The book was better.”

How many times has that phrase been uttered? Films and books are two different forms of media, and there is no reason why one should be better than the other. As long as films have been made, filmmakers have been turning to books for inspiration. And why not? There’s nothing wrong with going with the old book to film route, and as history as shown, it’s a coin flip, a toss up, it could go either way. There are so many things at work on any given film that when one is made well it’s a bona fide miracle.

Throw in a book with any sort of built in fan base and you got a whole new can of worms to dig into Fear Factor style (have they done that one yet? Cans of worms? Seems so obvious). There’s a bonus to having fans ready to see what someone did to their beloved books. There’s that whole Twilight thing. Anyone hear about these Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter movies? They appear to be some sort of a big deal, I dunno. Then again, sticking to the source material doesn’t always work. Nobody liked The Da Vinci Code. Anyone see Battlefield Earth? (seriously, anyone? I’ve yet to meet a person masochistic enough to put themselves through the whole thing). So making a book a movie, a time honored tradition, is a risky endeavor. Yet plenty of people have their stab at it.

Of course the Coen Brothers style was to adapt a book that wasn’t published yet. Built in fan base? Who needs one. Franchise film? Barking up the wrong tree. Top ten worldwide grosser? Nah, not here pal. The Coens make the movies they want to make, and often drop experimental films on an audience without them even realizing it. The stark whites of Fargo and the sepia tones of O Brother Where Art Thou culminated with their black and white opus The Man Who Wasn’t There. O Brother itself was an experiment in adapting a story (in this case The Odyssey) without actually reading the source material. Or so they claimed. Which is similar to how they told everyone Fargo was based on a true story, and later admitted that the story wasn’t exactly true, in that there was no case that the movie was based on. They just made it all up and said it was true. And why not? Stories like this happen all the time. Was it a true story? Well, you can be sure it was a story, and you can take from it what you will.

2007 saw the Coens drop a lil’ gem they like to call No Country for Old Men. And they called it that because Cormac McCarthy called it that. And that’s not all they adhered to. The Coens, who also wrote the screenplay, lavished their movie with the detailed attention usually reserved for ultra geeky arthouse films. So what happens when the work of a writer with a singular voice and a hatred for quotation marks is filtered through the sensibilities of two of the quirkier and independent filmmakers today? You get a movie that simply divides it’s audience, and for so many different reasons. But really, it’s all in the perspective. It’s all in what the viewer wants to take out of it.

I read the book after I saw the movie, though I was already a fan of McCarthy. And I was surprised by how similar the movie is to the book. Extremely similar. Sure, there are some third act diversions, but just about any book will go through that, as movie storytelling is a completely different monster from book storytelling. The Coens, however, only made the slightest of deviations from the third act, and this lack of deviation and devotion to the source material is what either sells or kills this movie for people. It’s the breaking away from conventions and cliches that throws people off. Some people don’t like when the rug is pulled from under them. But the Coens are sneaky about it. They mix their convention busting with just the right dose of movie cliche.

The first and second acts are pretty straight forward, and the usual Coens experimentation isn’t so in your face. First off, there is basically no score to this film. Films nowadays have music playing from front to back. Slumdog Millionaire was a collection of music videos! SluMTV. A majority of No Country plays out with no music, just natural ambiance and the sounds of a dangerous man walking in his socks. This helps suck in the viewer in the more tense scenes, as sound becomes very important in characters being able to locate each other and chase each other down. And with the exception of a faceless opening voice over, the protagonist of the film is not introduced until the second act when Sheriff Ed Tom Bell makes his first appearance (an oh so grizzled and world weary Tommy Lee Jones). The Coens are no stranger to this second act protagonist thing, having done the same with Police Chief Marge Gunderson in Fargo, and it worked out okay there too. And these near invisible non-conventions are balanced with typical movie stuff, like Moss (Josh Brolin) just happening across a cache of cash money in the middle of nowhere and later outrunning a truck for thirty seconds. Stuff like that happens in movies all the time without question. No exception here.

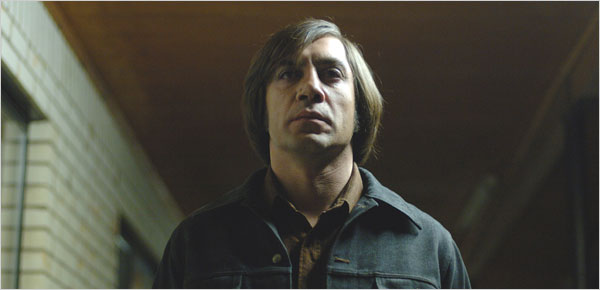

Javier Bardem played Anton Chigurh, a character that was the personification of violence. He struck out pretty randomly and without reason, and just about everyone he comes into contact with dies. Sometimes it’s for a reason, maybe only known to him but a reason nonetheless, and sometimes it’s for no reason. It’s because he needs the chicken truck. Or because the accountant was in the wrong place at the wrong time. Or because the coin flip came up tails. And even his character was not immune to violence, both with reason and random, and he barely makes it out of the story alive, though not in the way people expected. These characters are not all dying without reason, as in “this is a typical, violent Hollywood movie,” but are dying because that’s what the film is about, the violence humans inflict on each other for whatever reasons they have, and the violence inflicted on them. What hell hath we wrought and all that jazz.

Sheriff Ed Tom Bell, now in the twilight of his career, has seen the violence escalate to a point that he can’t handle anymore. From the very beginning, he’s a man who is avoiding extra responsibility. And by the end, he’s seen things that he wished he hadn’t seen, and it breaks him. He retires, disenchanted with the world and dreaming of his father making a warm place for him in the cold and dark world. And what he sees is what upsets people, the death of the character that we’ve been following with the money, barely ahead of Chigurh. But he’s blindsided by a third party, and Sheriff Ed Tom rolls up on the crime scene in media res and actually sees the culprits speeding away. Ed Tom runs out of his car and finds Moss dead. And this is the concession made by the Coens to the audience. In the book, McCarthy saw fit to kill off this character between chapters. He was alive on one page, then a couple of pages with someone else, and then Ed Tom gets a phone call telling him that Moss is dead or something along those lines. In the film, Ed Tom is checking in on Moss when this all goes down and he just misses it, and the viewer just misses this action as well. And it’s frustrating, for sure. But isn’t that what the best films do? Make the viewer really feel the protagonist’s emotions and empathize with their situation? The viewer gets that same sense of horrible frustration and helplessness as Ed Tom, and a lot of people simply hate that feeling. The rug was completely yanked from underneath them, and a central character was killed off screen by a third party, albeit an interested third party with plenty of obvious set up.

And the final scenes of Ed Tom are with him, retired and home with his wife, not sure of what to do with his day. The violence he has seen has weighed him down completely and crushed him, and he learns that it’s nothing new, this violence has been around since forever, and the only that changed throughout it all was him. He aged, and with that age came a heavy heart at the crumbling world around him, and he was at a loss to explain any of it anymore. So the story, both book and film form, end the same way: an old and broken protagonist with a bleak worldview, his only lesson learned that the world is what it is and all he could do in the end was survive it. Not exactly uplifting. People aren’t going to see this movie and get the same jolt they get with Slumdog Millionaire, but then again, that’s not what the Coens wanted people to do. They wanted people to think about what they’ve seen and dissect what’s on screen. And plenty can be made of the many themes at play throughout the story, but of course you can take from it what you will.

(Reposted from my original Examiner post here.)

#319 – Delicious ‘N Appetizing

#319 – Delicious ‘N Appetizing #551 – Neon Genesis Crespogelion

#551 – Neon Genesis Crespogelion #237 – Pretty Freakin Terrific

#237 – Pretty Freakin Terrific Florida Film Festival 2014 review: ‘Strike: The Greatest Bowling Story Ever Told’

Florida Film Festival 2014 review: ‘Strike: The Greatest Bowling Story Ever Told’

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.