It is incredible how often people decry implausibilities in movies, allowing themselves to be drawn out of a movie’s spell by questioning every little thing about a story and how it is presented, declaring a movie to be shit because they “didn’t buy it.” But why does this happen? When did “realism” become so important to movie going audiences? Did we decide that we were all going to stop believing? Who told us that Santa wasn’t real anymore? Why did our balloon pop and how did it happen? What the fuck happened to our childhood?

Okay that’s a little extreme. Let’s dial it back a bit and lay some groundwork here.

First off, what is this “realism” and how does it fit into movie making? Realism is best defined when considered along with its counterpart formalism, which makes for a stylistic yin-yang of storytelling modes. Realism presents itself as portraying reality, whether or not it is fiction, by showing the characters and setting in as straightforward a manner as possible. Whether this be a documentary or a family home video or a Christopher Guest mockumentary, things are (supposedly) presented as they are, as if someone just grabbed a camera and went outside and started filming life itself.

Meanwhile formalism includes things like editing, staging, production design and music, and when related to film, doesn’t have to include a story or even characters. Think of video installations at art galleries, little moody films that are supposed to be about abstract ideas conveyed through its presentation. Fantastical elements, things that can’t be found in real life, created specifically to be photographed in order to convey a mood or an emotion, that is formalism.

Now smash these two seemingly disparate styles together; birthed out of the tiny black hole that briefly opened up from such a smashing of styles has led to what we all know and love, and that is good old classicism. See, this is when we get movies about fathers and sons and foster parents and immigration and heritage, all very “real” topics and issues, but told through the guise of a comic book movie, filled with special effects and wall-to-wall music emphasizing the story and emotional beats of the film. Or movies about man eating great white sharks stalking a small beach town, or movies that take place a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, a long and distant time and galaxy that seems to have the same problems and issues as our own time and place now.

So most things that we consume today via cinema and television fall under classicism and it has always been this way. This goes back beyond movies to stories told on the stage, stories that mixed every day problems with high concept plots about revenge and retribution, with an occasional dose of some scornful or careless deity to move matters along a little more quickly. Either small stories could be dressed up by putting your actors in grand costumes and big sets and make their characters gods and demons and whatnot, or big, fantastic stories could be shown in as real a form as possible, presented as if these things could be really happening. Think of the documentary style approach to the sci-fi movie “District 9,” which is shown in a world that is meant to be taken as real as ours, just with the added element of this very real world also including giant aliens living on our planet with us.

Now as movies have evolved over the last 120 years or so, audiences’ tastes and expectations have changed along with the times. As filmmakers got better at actually capturing the world around them and presenting it to people on a giant screen, those same people expected more from their filmmakers. Think of the acting over the years. Back when movies didn’t have sound and dialogue couldn’t be played back to people, the artists involved had to paint their pictures in broad strokes in order for them to be understood more clearly. As sound was added and actors were expected to actually talk in their movies as well as stand there and look pretty, the acting was pretty stiff across the board, and this was because many of these actors came from the boards; many movie actors started in theater, and many theater productions call for actors to play their roles “for the back row of the theater,” meaning everything has to be big and loud and deliberate enough for absolutely everyone in a theater to understand what the actor is conveying.

This of course is unnecessary in movies, in which the distance between the actors and the audience is already predetermined by the placement of the camera, but for whatever reason it took awhile for a lot of actors to realize this. This may be why someone like Humphrey Bogart was so insanely popular in the 1940s and 1950s because he did have a more toned down and “realistic” bag of tricks in his portrayals than most of his boisterous, over enunciating contemporaries. And then Marlon Brando came along and changed the way people saw the craft of acting. Brando showed that you could go small, you could be intimate and real with your performance, you didn’t have to play to the back row because that row doesn’t exist outside of the theater. And acting changed, it slowly became more naturalistic, less stylized, more real. So it has been with every aspect of filmmaking throughout the years.

So when we’re talking about realism in movies these days, are we actually talking about authenticity? If it has the feeling of being real and is presented as real, will it be accepted, even if its blatantly not? Again, the aforementioned immigrant son dealing with his heritage and parentage, whom audiences know is from another planet that really even exist, audiences will sit down and watch this story and they will be able to parse out the over the top fantasy elements from the more character driven moments, and really in the end all they want is the same level of authenticity from beginning to end.

Because there is still that element of suspension of disbelief – as we sit down in a theater to watch a movie, we know it’s not real, we know we are watching a rapid succession of still images that create the illusion of movement, we know that we are watching light projected onto a screen, and that the actions are not really unfolding right before our eyes magically. We understand movie magic. As an audience we enter into a pact with the filmmaker, a complicit understanding that we are seeing a piece of art, worked up by a crew of people, and thus the entrance of that suspension of disbelief. So when someone sees something in a movie that “pulls them out of the story,” what actually happened? Why did this suspension bridge between the viewer and leaps of logic required by the art collapse in the middle and fall in the cold, choppy River of Betrayal.

On the filmmakers’ side, this failure comes from the lack of obeying to the rules of the world they created. This world building can happen consciously or subconsciously, and usually the best artists pay attention to this aspect of their creations. Depending on the genre in which one is working, there is more or less leeway in creating a world that differs from the one in which we live. When it comes to big idea genres like horror and science fiction, it is much easier to set up a world in which crazy things are happening so they can suit your story purposes, because these things are expected in these genres. People go into horror movies expecting zombie hordes or monsters or aliens, and they watch sci-fi movies because they want to see movies that take place in far off planets or in the future or whatever. The key is, when creating one of these stories, no matter how fantastic the world is, when you set up the rules of this world, you have to stick to these rules, and if you break them, you lose the audience. You can have a movie about a super powered alien coming to Earth and living among us, but once you establish who this character is within this world, i.e. his demeanor, behavior, motivations, desires, you can’t just decide to suddenly change just to fit your plotting, he has to continue to be portrayed as the character you have created, in the world you created.

Action movies similarly allow for that leeway in world building and character creation. Like kung fu movies in which there are supreme masters who have perfected kung fu to the point of being able to levitate or do other crazy things, these things are established in these cinematic worlds, and audiences have grown to even expect them. Look at how those “Fast and Furious” movies have just become more over the top and ridiculous, with physics-defying action and spectacle that audiences have now come to both expect and demand. But stick to the rules! You can’t have Vin Diesel’s character jumping off cliffs and over bridges and doing other super human acts, constantly defying death, only to die when he is gently rear ended at a stop sign and his air bag deploys and hits his face in such a way that it rocks his head back and breaks his neck. Audiences would revolt at such a mistreatment of a character that has already been through so much and has apparently proven time and again that he is impervious to all thing including death and logic.

Straight drama, meanwhile, is the toughest to change on audiences, because when you are just telling a basic story about people in a real world setting, audiences are going to recognize that setting and they are going to imprint themselves immediately on what they see, relating the world of the movie to the world around them, which means if the characters act or behave in a way that a particular member of the audience might not be able to empathize with, then we have a dramatic impasse. At the end of the day, reality is subjective, and the people in your “world” won’t act the same as the people in my “world,” and this can easily extend to the world of a movie. We quickly understand that Travis Bickle is a mentally deranged and possibly dangerous person within ten minutes of “Taxi Driver,” yet no one would have believed if the movie ended with this character simply having a change of heart after being rejected by his lady crush and instead of going murder psycho crazy Travis just decided to “get his life together” and went to school and got a teaching degree and now he works with kids, the end. That’s a betrayal. You can’t set up this character in one way and then suddenly and without cause change him at your own whim as an artist, because then your just fucking with the audience, and they do not like that one bit.

But that is just one side of the coin. Who is to say that audiences are not culpable in this betrayal? The pendulum swings both ways, and sometimes it is not the filmmakers breaching the pact but instead it is the audience member, scratching his (or her) head instead of just enjoying the movie on its own terms (these terms being the already established rules of the world). Sometimes an audience member just wants to point at one little thing and hold it up as the finest example of why the whole movie has fallen apart, and usually the smaller and more insignificant the offending detail, the more the offended yells and hollers. This is usually referred to as nit-picking.

Quick personal anecdote for reference sake: who goes to a Roland Emmerich movie expecting complete realism and real world authenticity? Fools, that’s who. “The Day After Tomorrow” and “Independence Day” are prime examples of movies in which suspension of disbelief is an essential. Yet when I saw “2012” in theaters, a movie that featured such aggressive global warming that it caused the Earth’s magnetic poles to shift, an audience member seated behind me took umbrage to a scene in which a limousine outruns an earthquake – specifically, when the limo approached a giant crack in the highway and then proceeded to jump that gap and ride on to safety, this audience member let out an audible “Give me a break!” as he was clearly exasperated with this bit of physics-defying onscreen action.

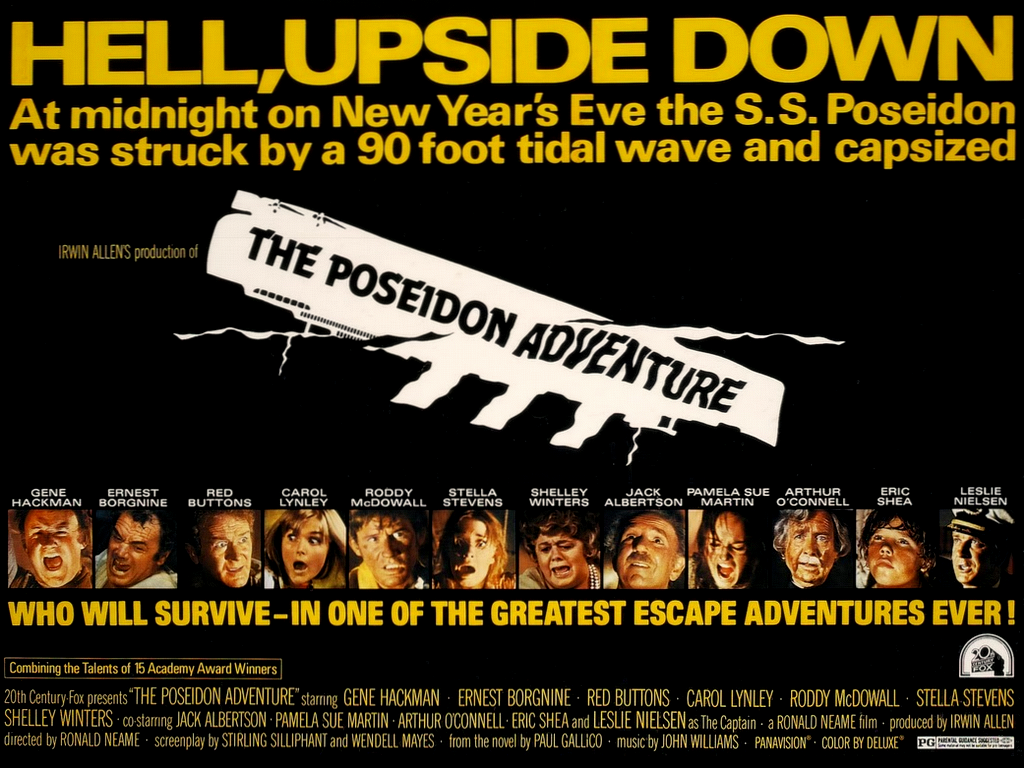

To which I wanted to say well what the hell were you expecting in a B-level disaster movie? Were audiences guffawing at 1970’s stalwarts (and certified pieces of shit) like “The Towering Inferno” and “Earthquake” and “The Poseidon Adventure?” And please keep in mind that I am not advocating the whole “check your brain at the door/turn off your brain/any kind of brain as light or detachable body part saying” idea, as I fully believe that even the dumbest movies still need to work if you think about them, and for example there is absolutely no need to “turn off your brain” when watching movies like “Dumb & Dumber” or “Predator,” which are very base and ridiculous movies but are still very well made and can be rewarding when you actually dig past their genre exteriors and discover, gasp!, that there is actually something there!

Instead of nit-picking, and instead of lobotomies, there is another option for audiences, another way for them to be able to sit back and let movies be movies without having to expect real world believability at every turn, and that’s acknowledging that movies are actually loaded with dream logic, which is in stark contrast to real world logic. You know that when you dream, weird things happen all the time, and you don’t question it as happens, nor does it seem weird. It just happens, and as the dreamer, you get caught up in it. Settings change, people appear and disappear, fantastic and outlandish things happen, and you keep moving forward, because it’s a dream and that’s how dreams work.

And if you’ve seen Martin Scorsese’s “Hugo,” then you know that one of cinema’s originators George Méliès believed that movies were the stuff of our dreams and that is where they came from, and that is so true, as the place where our brains come up with these crazy dreams and ideas is the same place where we can come up with these fantastic images to turn into moving pictures. And of course now we’ve all experienced the weird feeling of dreaming that we are in some sort of movie, and now we have a cycle of dreams turning into movies turning into dreams, and if we just let this feedback loop really get going and stop trying to muck up the works with real world logic and authenticity, then who knows what kind of marvelous and out of this world movies could be made and enjoyed?

Are we holding ourselves back?

Bonus Episode – Oscar Picks 2017

Bonus Episode – Oscar Picks 2017 Review: ‘Beasts of the Southern Wild’

Review: ‘Beasts of the Southern Wild’ Crespodiso Film School – Bruce Lee

Crespodiso Film School – Bruce Lee #452 – Geometric Elegance in Chaos

#452 – Geometric Elegance in Chaos

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.