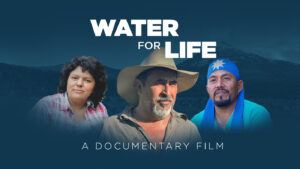

Twelve years in the making, Water for Life features three Latin American community leaders working to protect their water and ancestral territory from multinational corporations and corrupt governments that threaten the environmental, cultural and economic survival of their communities. Narrated by Diego Luna, Water For Life will have its Orlando premiere at the Florida Film Festival on Sunday April 14, and will screen again during the festival on Friday, April 18. In this interview with producer and director Will Parrinello, he discusses how he chose these three leaders to feature in the film, the process of making this film, and his hopes for what the movie can accomplish in terms of spreading awareness of these environmental battles and the people caught up in these fights.

Twelve years in the making, Water for Life features three Latin American community leaders working to protect their water and ancestral territory from multinational corporations and corrupt governments that threaten the environmental, cultural and economic survival of their communities. Narrated by Diego Luna, Water For Life will have its Orlando premiere at the Florida Film Festival on Sunday April 14, and will screen again during the festival on Friday, April 18. In this interview with producer and director Will Parrinello, he discusses how he chose these three leaders to feature in the film, the process of making this film, and his hopes for what the movie can accomplish in terms of spreading awareness of these environmental battles and the people caught up in these fights.

Chris Crespo: What was the process of choosing these three people as your main subjects to tackle this issue of water use and land rights throughout Latin America? Did you initially want to make a documentary about this problem, or did you find out about the individuals first and then learned about their cause?

Will Parrinello: As independent documentary filmmakers, director of photography Vicente Franco and I have been making short documentary profiles of Goldman Environmental Prize recipients throughout Latin America since 2009. Each year the Prize, often referred to as the Nobel Prize of the environmental world, recognizes six grassroots environmental defenders from around the world who have achieved a seemingly unachievable goal. I wanted to make this film because I found these stories to be incredibly inspiring. At a time when we face numerous environmental challenges, many which seem insurmountable, here are stories of individuals who are courageously standing up, speaking truth to power and creating positive change in the world!

In 2010, when Vicente and I were flying home from El Salvador, having filmed Francisco Pineda’s story, we knew we had to make a longer film about him. The idea was borne from the visceral experience we had feeling Francisco’s quiet strength, his courage in the face of overwhelming odds, which was undeniable. So the idea was first, to film a portrait of him, the man, not the environmental champion. But at the same time, the two were inextricably bound together.

The anti-mining movement, which he played a key role in creating, gained incredible momentum in a very short period of time in the run up to the 2009 presidential elections. Media polls showed that 80% of the population was against gold mining. The sitting president, having termed out, knew that his conservative party’s candidate was polling well behind the charismatic leftwing candidate, so he banned all metal mining. This led to Pacific Rim Mining Corporation to sue the government of El Salvador in the World Bank Court for $250 million dollars. Within one year, three anti-mining proponents, all friends of Francisco, were murdered. It’s said that life is cheap in El Salvador, when billions of dollars of gold are at stake.

Through our initial work on the Prize films we established strong working relationships with our three protagonists. Over the ensuing years of filming, 12 in El Salvador, eight in Honduras and six in Chile, our relationships, and the trust between us deepened to the point where, at times we felt like we were part of our protagonists’ families.

CC: This movie covers a twelve-year span of time, and while the documentary does have a sense of conclusion, it is clear that these battles will continue as long as these transnational corporations are around. What factored into your decision to end the documentary when you did and put it together for this festival run?

WP: We always knew we were in this for the long haul. But we were convinced that our protagonists would persevere, and win their battles, so we committed to taking the long road, waiting for each of our three story’s victories.

But of course, these struggles never end. As Francisco Pineda says in the film, referring to Pacific Rim Mining Corporation, It’s a sleeping monster, waiting for the right moment to return and catch us by surprise. As we speak, El Salvador’s President is beginning to make noise about rescinding the country’s precedent setting law banning metal mining. He claims mining is necessary for the country’s economic growth. While the country would undoubtedly benefit from economic growth, the cost to subsistence farmers is what drove them to the streets to protest mining in 2008.

In El Salvador, it took nine years for Francisco’s story to reach its natural conclusion – when the government of El Salvador enacted anti-mining legislation. Then, the Attorney General beat back Pacific Rim Mining Corporation’s $250m claim in the World Bank Court, where Pac Rim maintained that El Salvador’s refusal to let it mine gold caused huge losses in potential profits. The court determined that Pacific Rim failed to meet regulatory requirements for the requested mining permits. They also lacked crucial environmental permissions, did not hold the rights to much of the land required for its project, and failed to submit a proper feasibility study and environmental assessment.

In Honduras, Lenca leader Berta Cáceres was murdered after stopping construction of a hydroelectric project on her Indigenous people’s sacred Gualcarque River. It took six years before eight of the nine men accused of plotting her assassination were convicted of murder. Cáceres’ children believe that Daniel Atala, the Chief Financial Officer of the hydroelectric power company, a member of one of the most powerful families in Honduras, was the chief architect of their mother’s murder. With evidence revealed by an investigation instigated by Cáceres’ family, authorities issued a warrant for Atala’s arrest in connection with Berta’s murder. With the noose tightening around his neck, he has fled the country.

In Honduras, Lenca leader Berta Cáceres was murdered after stopping construction of a hydroelectric project on her Indigenous people’s sacred Gualcarque River. It took six years before eight of the nine men accused of plotting her assassination were convicted of murder. Cáceres’ children believe that Daniel Atala, the Chief Financial Officer of the hydroelectric power company, a member of one of the most powerful families in Honduras, was the chief architect of their mother’s murder. With evidence revealed by an investigation instigated by Cáceres’ family, authorities issued a warrant for Atala’s arrest in connection with Berta’s murder. With the noose tightening around his neck, he has fled the country.

After stopping two illegal hydroelectric projects on his people’s Indigenous ancestral lands in Southern Chile, Mapuche Chief Alberto Curamil was arrested and incarcerated for 15 months on false charges of armed robbery. Authorities sought to imprison him for 50 years, despite no physical evidence linking him to the crime based on an anonymous phone call. Supporters said the charges were aimed at silencing his activism. With the support of many international environmentalists, Curamil was finally acquitted of all charges and released from prison. Two years later, while leaving a peaceful protest, Alberto was shot in the back three times, at point-blank range by police officers assumed to be part of an ultra-right wing nationalist group. We chose to omit this dramatic episode from our film because it was simply one too many story beats. When this occurred in April 2021, we launched an impact campaign with support from Amnesty International Chile to protect and defend Curamil. Led by two Goldman Environmental Prize Laureates, Amnesty launched a petition campaign.

They also landed an OpEd in the Washington Post and a feature article in The Guardian, which helped generate thousands of signatures for Amnesty’s petition, demanding an independent investigation into Curamil’s shooting. The campaign succeeded, with the authorities and ultraright wing group leaving Alberto, his family and community alone, ever since.

CC: Clearly this film is meant to spread awareness of the fight happening in these places and others like them between people and corporatized interests, so what do you hope viewers will do once they see Water For Life?

WP: Water For Life is a story of courage and determination, betrayal and corruption, death threats and murder, and of unexpected victories in the countryside and in the courts. It is a story that asks how economic development can grow in harmony with environmental protections and why we tolerate unbridled greed and profiteering at the expense of human life and our precious planet. The film illuminates a growing recognition of Indigenous rights and a rising demand for corporate responsibility and environmental justice that’s being seen around the world. It is a story that begins and ends with water.

My hope is that Water For Life will inspire audiences to take action in their own communities, to create the change they want to see. Alberto, Berta and Francisco would encourage us all to get involved in issues that matter to us, pointing out that real change – social, economic and political – really only takes place from the ground up, grassroots style. I’m no Pollyanna, I understand that these were not easy victories. Each of our protagonists, their families and communities paid a price for their struggles, but the key is they carry on, always have, always will. We end the film with a shot of Berta’s tombstone, the inscription on it are her words, “Wake up humanity, there is no more time!”

CC: Are you already working on your next project, or are you just focusing on the future of this film right now? What are your hopes for the distribution of Water for Life?

WP: Our filmmaking team just completed six short profiles of the 2024 Goldman Environmental Prize recipients. At the same time, we’re taking Water For Life on the international film festival circuit, with upcoming screenings in Brazil, Chicago, Cuba, Italy, Mexico, San Diego and Spain. While we wait to see which other festival we’ll be invited to, we’re also rolling out our impact campaign, hosting community and educational screenings. Amnesty International is one of our impact partners as is the RFK Human Rights Center. We’re confident we’ll screen at many more festivals over the next 12 months, leading up to our National PBS broadcast on or around Earth Day, 2025. In the meantime, we’re seeking international distribution for the film, in all territories outside of North America. We would love to work with Amazon Studios or National Geographic/Hulu. Fingers crossed!

Chris Crespo is a movie critic, writer and podcaster based out of Orlando, Florida. He hosts the weekly podcast Cinema Crespodiso, and has also made appearances on Doug Loves Movies, A Mediocre Time with Tom and Dan, The Curtis Earth Show, and more. This is his 14th year covering the Florida Film Festival.

This interview was conducted via email.

Netflix pick for 2/24/14 – ‘The Untouchables’

Netflix pick for 2/24/14 – ‘The Untouchables’ Review: ‘Krampus’

Review: ‘Krampus’ #370 – Who is Christmas Cena?

#370 – Who is Christmas Cena? Spoiler Bonus Episode – Spider-Man: Homecoming

Spoiler Bonus Episode – Spider-Man: Homecoming

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.